Serigraphy - Hybridity in Resurgence

Warhol screen printing. Photo credit: King & McGaw

from Adverts to high Art

Screen printing has an ancient history stretching back to China in the Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD). The technology as we know it now – with a frame holding stretched silk fabric and the use of photographic emulsion coating to create a stencil which the ink is then forced through with a rubber squeegee– was not developed until the early 20th century. Since it was a quick and efficient way to create and replicate graphic media, this method was primarily used in advertising - such as posters.

By 1938, it had been adopted by a group of artists known as the National Serigraph Society who renamed it “serigraph” (a term meaning “seri” silk in Latin and “graphein” to draw in Greek) to separate it from its original industrial context. Its popularity in the modern art continued to grow especially in the 1960s anti-establishment Pop movement with works such as Andy Warhol’s iconic Soup Can prints (1962).

West Coast Hybridization

This medium made its way to the west coast art scene through institutions such as Gitanmaax School of Northwest Coast art at K’San (Hazelton), Camosun College and the Vancouver School of Art where it quickly became a new “tradition” among First Nations’ artists. When it was originally introduced artists created quick and cheap prints for the tourist trade and ceremonial use (as potlatch gifts and personal cards), but by the late 1970s these works became more valued by art collectors and a distinctive market developed.

In 1977, the creation of the Northwest Coast Indian Artists Guild, the use of archival quality paper and the more rigorous adherence by artists to the creation of “limited edition prints” contributed to this change greatly. Limited edition prints are (like the names suggests) only given a limited number of reproductions, each signed and numbered by the artists thereby giving the prints a collectible quality.

Catalog of the 1977 graphics collection featuring works of renowned artists such as Robert Davidson, Joe David, Gerry Marks, and Francis Williams.

Cultural Resurgence

Nuu-chah-nulth artists, such as Joe David, Tim Paul, Art Thompson, and Ron Hamilton, used this medium to explore and articulate a distinctive Nuu-chah-nulth style separate from the Northern styles of the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw, Haida, and Tsimshian. This was an important departure for modern Nuu-chah-nulth art.

Printing allowed for artistic experimentation and was more accessible to the buyer than carvings and other traditional (less portable) art works. This opened a space for Nuu-chah-nulth artists to influence the Pacific Northwest art scene in a way it had never done before.

Four Prints Considered – A Cross-Cultural Analysis of form

Raven is often called the light bringer for the knowledge he brought to humans. Let us use him here to shine light on a comparison of form between Nuu-chah-nulth, Haida, Kwakwaka'wakw, and Tsmishian styles.

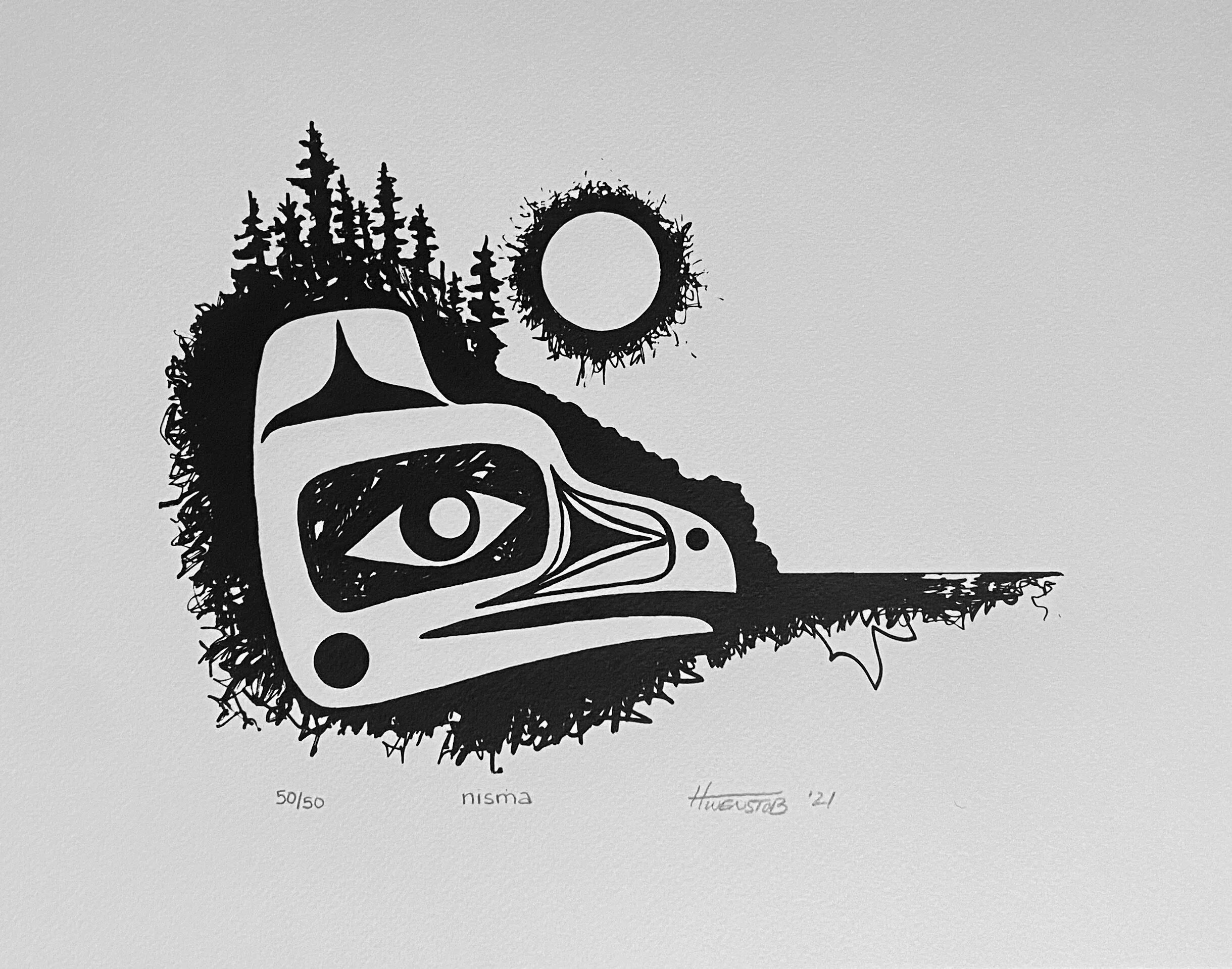

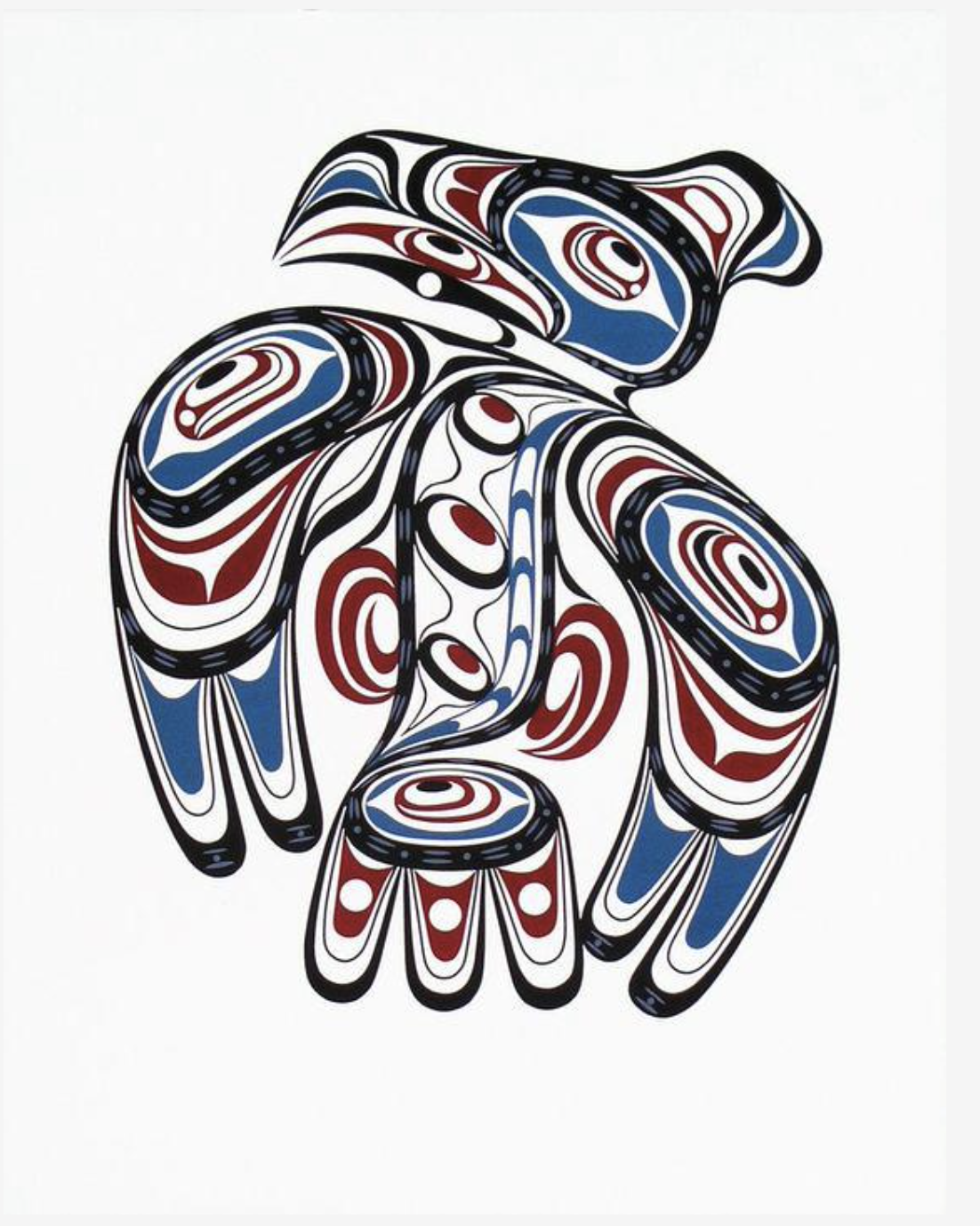

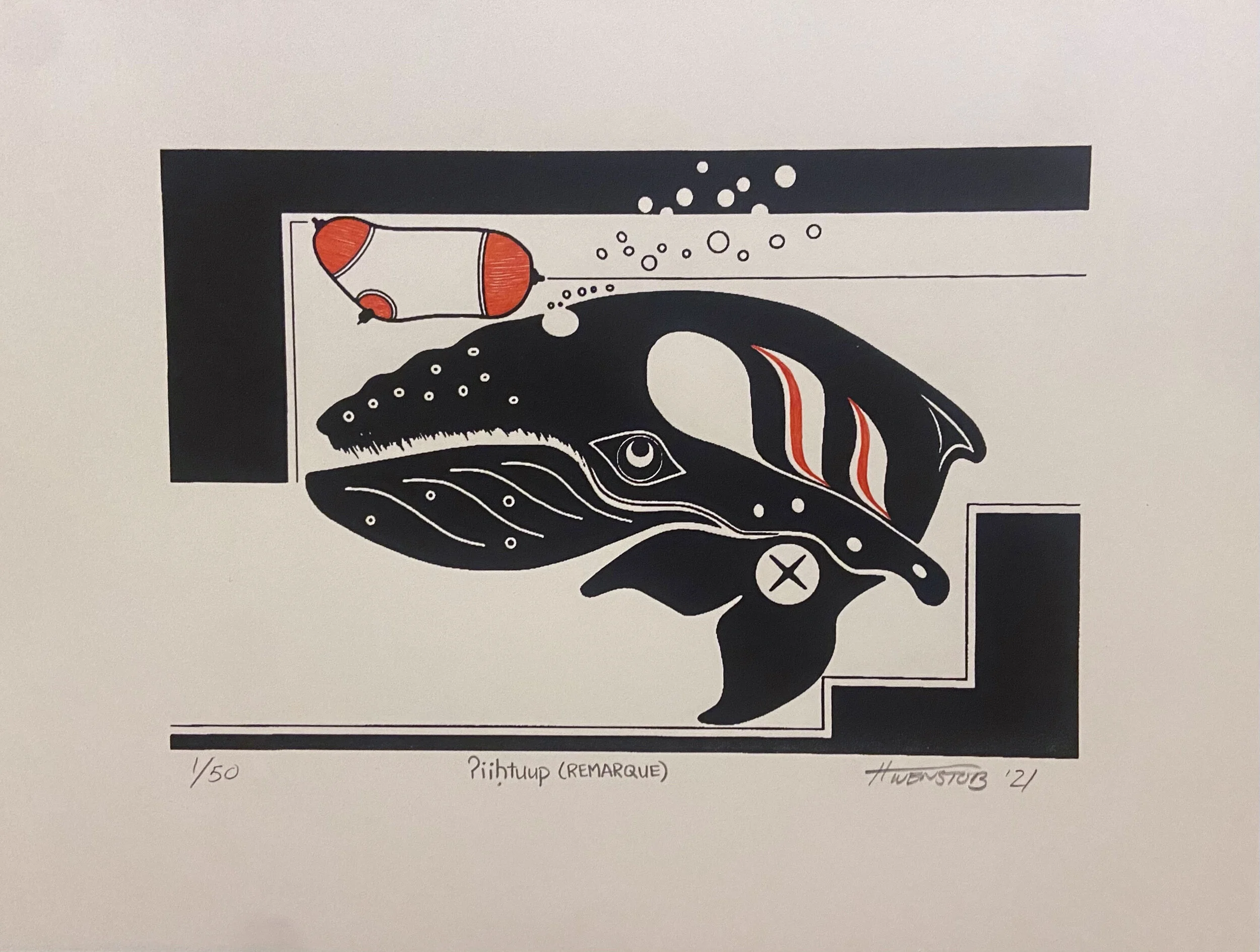

Consider the four very different prints of a raven (above and below). Patrick Amos’s work highlights the Nuu-chah-nulth more realist style . This is typified by his use of organic, less rigid form-lines in his depiction of the feathers along the outside of the raven and in the face of the moon. Bill Reid’s raven, is much more fine in line and is highly stylized, which is iconic of Haida work. Both Nuu-chah-nulth and Kwakwaka'wakw works are known for their use of bright and unusual colours, such as the blues and the green seen here. Tom Hunt’s swirls and filled-in spaces demonstrates the Kwakwaka'wakw tendency for a greater elaboration of detail. Contrastingly, David Boxley’s work shows how the Tsimshian specialize in a subtlety and an understatement of design –such as the colour reversal seen in the torso of the raven.

Sources:

India Young. 2012. “Re-Pressed: How Serigraphy Re-Envisions Northwest Coast Iconography.” ARTiculate Vol.1:Spring, University of Victoria. Pp. 39-54.

Hall, Edwin S., Margaret B. Blackman, & Vincent Rickard. 1981. Northwest Coast Indian Graphics: An Introduction to Silk Screen Prints. Douglas & McIntyre: Vancouver.

January 27, 2014. “Printmaking Terms” from Native Art Prints by Lattimer Gallery.

September 19, 2018. “What is Serigraph Printing?” from the Cedar Hill Long House Native Art Prints.